Opinion. Adnan Jaswal, Board Member, Her Place Museum.

In the 1840s, Ada Lovelace – a female mathematician – became the world’s first computer coder and, critically, conceptualised the difference between what a calculator does and what a computer could do. One crunches numbers, the other changes the world.

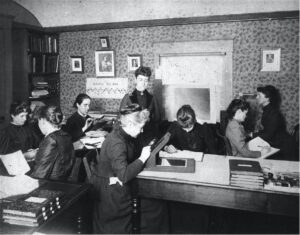

At the beginning of the 1900s in Australia, 72 women, including Prudence Valentine Williams and Dr Dorothea Klumpke, were employed to measure the location of stars as part of the ambitious Astrographic Catalogue – and became known as ‘computers’ themselves in doing so.

During WWII in the 1940s, Kathleen McNulty, Jean Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Frances Bilas and Ruth Lichterman were hired by the US government to program ENIAC, the first programmable electronic computer.

And Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughn and Mary Jackson, only very recently acknowledged in the film Hidden Figures, worked at NASA processing critical aeronautical data as the US rushed to get to the Moon.

All of the accomplishments of these women happened at times when gender, race, family and societal expectations made working in STEM harder for them than for men. Not only were these women rarely acknowledged for their contributions, they faced conditions that their male peers did not.

Things get worse, not better

History is full of these women. Yet, instead of becoming more and more involved in tech as society progressed, women were seen less and less. Not just because, as before, they were forgotten or hidden, but because increasingly, they weren’t allowed to exist.

In the 1980s, women in US computer science degrees reached nearly 40%. By 2008 it had fallen to 17%. In Australia, according to the Second National Data Report on Girls and Women in STEM, women made up less than a quarter of STEM students in 2019.

Since 2015, women enrolled in STEM fields of education in Australia has increased by 2%, the numbers working in STEM-qualified industries and in management roles are also going up, albeit slowly. Educationally speaking, things are getting better. But once women enter the workplace in these roles, they are more likely than their male peers to leave them.

Five years post graduation, men with a STEM qualification are 1.8 times more likely to be working in a STEM role in Australia. And when The Pew Research Center polled women in technology roles in 2017, they found that 50% had experienced gender discrimation at work. Only 19% of men said the same. In computing and male-dominated workplaces, the numbers were worse. One only has to look at the string of Silicon Valley sexual harassment suits over the last decade to know there is a systemic underlying problem.

Even women who try to forge their own path by creating their own companies face an uphill battle. Shanea Leven co-founder and CEO of CodeSee developer platform, recently proclaimed that “raising money is catastrophically challenging for female founders, and even harder for Black female founders.”

She isn’t wrong. Just 1.9% of enterprise software companies with at least one female founder received VC funding according to a recent report from Work-Bench. Of startups more generally, only 25% of those receiving funding included a female founder.

Why it matters to all of us

The craziness of these numbers is not just about equality (though that is of course a crucial goal in itself) – as Work-Bench notes, female-led teams generate 35% higher return on investment than all-male-led teams.

Diversity has been shown, over and over again, to benefit organisations and society. One study found that when female leadership was lifted by 30%, it led to an average 15% rise in profitability. With a diverse workforce, talent options are better, insights greater, innovation more productive and the business more successful. It simply makes logical sense that more women in tech leads to better outcomes for everyone.

Last year, an event on women in the digital era discussed how to get more women into the digital and wider economy. Women need to contribute to – and benefit from – the digital transformation the world is undergoing. If female participation is not increased, then the risk of their discrimination goes up. It’s a complex problem and it needs to be properly understood in order to remove obstacles.

One of those obstacles, and perhaps part of the reason I, a man, am writing this piece, is in perception. Women are still seen as being more burdened by ‘work-life’ inflexibilities (read: raising children) – this has been especially so during the COVID pandemic.

But tech companies are still predominantly run and staffed by men. The options, tools and flexible ways of working, given to women, given to them – or not given – by men. To change this, men have to be part of the solution.

It’s time to make better choices.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ada_Lovelace

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2019-12-01/women-computing-astronomy-technology/11713282

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Astronomer_Edward_Charles_Pickering%27s_Harvard_computers.jpg

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/13/magazine/women-coding-computer-programming.html?utm_source=pocket_mylist

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marlyn_Meltzer#/media/File:Reprogramming_ENIAC.png

- https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/sep/05/forgot-black-women-nasa-female-scientists-hidden-figures

- https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_325.35.asp

- https://www.industry.gov.au/news/second-national-data-report-on-girls-and-women-in-stem

- https://www.cio.com/article/201905/women-in-tech-statistics-the-hard-truths-of-an-uphill-battle.html

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-39025288

- https://techcrunch.com/2022/01/15/raising-money-is-catastrophically-challenging-for-female-founders/

- https://techcrunch.com/2021/12/09/work-bench-report-finds-just-1-9-of-venture-investment-going-to-female-enterprise-founders/

- https://www.piie.com/system/files/documents/wp16-3.pdf

- https://www.theparliamentmagazine.eu/news/article/embracing-equality-in-a-digital-era